“Jo Jones discovered that he could play the flow of the rhythm, not its demarcation.” – Martin Williams

“… if you listen to Elvin Jones first, you’ve got a problem. He was an original, but behind that originality lays every great drummer in Jazz. … many young people are trapped in the mystique of John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and never get any farther than that. Trying to play like Elvin is the worst thing you can do if you haven’t checked out his sources.” – drummer Kenny Washington

“The cruel fact is that a drummer’s fate rises or falls with the musicians around him. If no one listens to Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Coleman Hawkins, Tommy Dorsey, Roy Eldridge, or Lester Young, no one will hear the drummers behind them. They become stranded in recent history – that zone of cultural memory that lays just beyond the frontiers of nostalgia where scholars begin to outnumber witnesses.” – John McDonough

“One thing for sure. Anyone who plays drums or supposedly appreciates drumming should experience Jo Jones.” – Buddy Rich

The setting for this happenstance was the 1957 Newport Jazz Festival.

In those early days of its existence, the event was called the “American Jazz Festival at Newport, Rhode Island” and the gathering place for most of the musicians and dignitaries participating in the festival was Newport’s Hotel Viking.

Both sides of the entrance to the hotel are adorned with covered porches and it was there on that sweltering Independence Day in 1957 that someone sitting in a oversize, white rocking chair called out to me as I was walking up the stairs to enter the hotel: “Hey, little Mister, do you like Jazz music?”

The man calling out this inviting salutation had a broad smile that seemed to engulf his entire face. His eyes appeared to be gleaming with the joy of life and his manner of dress was, in the parlance of the time, swanky.

The man calling out this inviting salutation had a broad smile that seemed to engulf his entire face. His eyes appeared to be gleaming with the joy of life and his manner of dress was, in the parlance of the time, swanky.

And so it was that I got to shake hands with the great Jo Jones and from that moment on, the drumming of Papa Jo Jones entered my life and it has never left; forever imparted in my psyche. For as Dr. Bruce Klauber has so aptly stated.

“If Max Roach and Kenny Clarke are considered the fathers of modern drumming, then Jonathan “Jo” Jones has to be the godfather. By way of his work with Count Basie’s band from 1936 to 1944 and 1946 to 1948, Jones redefined the concept of a drummer. He lightened up on the four-beats-to-the-bar standard of bass drum playing, was possibly the first to use the ride cymbal as the main timekeeping accessory, and did things with the hi-hats that are still being studied today. Jones’ ability as a melodic and humorous soloist reminds one of a virtuoso tap dancer who makes everything look easy. Jones continues to be a major influence on everyone who played–and plays–drums.”

Here’s more about Jo Jones as expressed in this brilliant short essay by the peerless Whitney Balliett from his Dinosaurs in the Morning. [Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1962, pp 61-67].

© Whitney Balliett, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Jo Jones, dms.”

“ONE of the minor legends of jazz, which has a mythology as busy as the Greeks’, credits Jo Jones, the forty-eight-year-old Chicago-born drummer, with single-handedly setting off, in the late thirties, the revolution in drumming since blown forward by Kenny Clarke, Max Roach, Art Blakey, Philly Joe Jones, and Elvin Jones. This theory holds that Jo Jones was the first drummer to use his bass drum for accents as well as for a timekeeper, the first to shift his other accompanying effects to his cymbals, and, all in all, the first to develop a whistling-in-the-morning attack that made most previous drumming resemble coal rattling down a chute.

Nonetheless, several contemporary drummers were doing many of the same things, and not necessarily because they knew Jones’s work. (A highly regarded legendizing process in jazz is the convenient device of linking musicians with similar styles. Thus, John Lewis was once firmly informed that he resembled the late Clyde Hart, an economical and original pianist who was an indirect founder of bebop. Lewis replied that be had never heard Hart, in the flesh or on records.) Among these drummers were Chick Webb, whose work on the high-hat and the brushes is among the permanent ornaments of jazz; Alvin Burroughs, an adept, clean, nervous performer, who played as if on springs; O’Neil Spencer, who had much in common with Burroughs; Sidney Catlett, whose cymbal patterns, singular snare accents, and free-floating foot pedal were neater and snappier than Jones’s; and Dave Tough, who often implied even more than Jones and whose cymbals, in particular, had a splashing clarity. But any disagreement with the theory about Jones’s supposed pioneering is leveled not at him but at his admirers, who, like all jazz appreciators, are full of imagination. One of the handful of irreplaceable drummers, he stands -since Webb, Catlett, Burroughs, Spencer, and Tough are dead and most of the rest of his contemporaries are either inferior or in decline – as the last of a great breed.

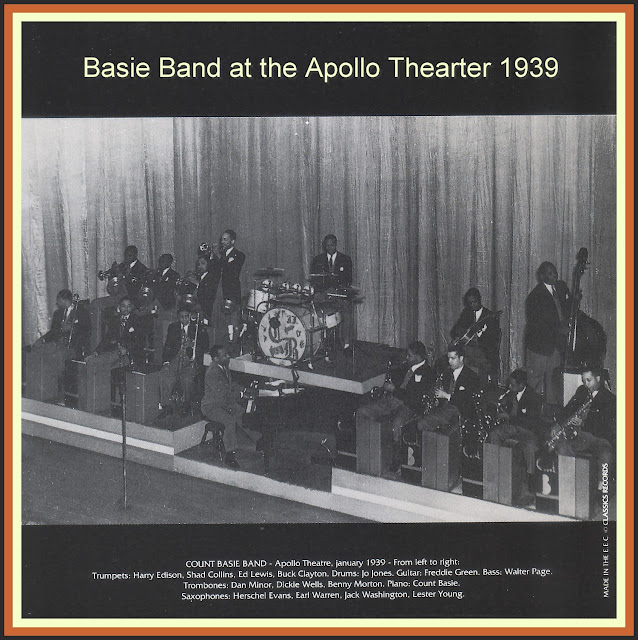

One reason for Jones’s over-glorification as a pioneer was his membership, from 1936 to 1948, in the Count Basie rhythm section, which included – in addition to Basie and Jones – Freddie Greene and Walter Page. This Basie rhythm section was classic proof of the powers of implication, for it achieved its ball-bearing motion through an almost Oriental casualness and indirection, as if the last thing in the world it wanted was to supply rhythm for a jazz band. The result was a deceptive sailing-through-life quality that was, like most magic, the product of hard work and a multi-layered complexity that offered the listener two delightful possibilities: the joint less sound of the unit as a whole, or, if one cared to move in for a close-up, the always audible timbre of each of its components. And what marvelously varied timbres they were! At the top was Basie’s piano, which, though most often celebrated for its raindrop qualities, attained its relaxed drive from a skillful pitting of loose right-hand figures against heavy left-hand chords. On the next rung came Greene, a peerless rhythm guitarist, whose Prussian beat, guidepost chords, and Aeolian harp delicacy formed a transparent but unbreakable net beneath Basie. Page, who had a generous tone on the bass and a bushy way of hitting his notes, gave the group much of its resonance, which was either echoed by Jones’s foot pedal and snare or diluted by his cymbal work.

And what marvelously varied timbres they were! At the top was Basie’s piano, which, though most often celebrated for its raindrop qualities, attained its relaxed drive from a skillful pitting of loose right-hand figures against heavy left-hand chords. On the next rung came Greene, a peerless rhythm guitarist, whose Prussian beat, guidepost chords, and Aeolian harp delicacy formed a transparent but unbreakable net beneath Basie. Page, who had a generous tone on the bass and a bushy way of hitting his notes, gave the group much of its resonance, which was either echoed by Jones’s foot pedal and snare or diluted by his cymbal work.

But the group’s steady tension also derived from the way its members counteracted each other’s occasional lapses. When Page’s sense of dynamics or harmony gave way to overly vibrant or bad notes, Basie might blot them up with his left hand or release a spray of upper-register exclamations. When Greene’s perfection seemed tediously precise, Jones’s accents or Basie’s unpredictability offset it. And when Jones occasionally grew heavy, slowed down, or raised the beat, Page, Basie, and Greene would head resolutely in the opposite direction. Most important, the Basic rhythm section dedicated itself to the proposition that each beat is equal, and, knee-actioned, wiped out both its own bumps and those handed down by all past rhythm sections. Although the group broke up more than a decade ago (only Greene remains with Basie), its low-key drive continues to seep into the four comers of jazz. And Jones, who has since worked with all types of jazz musicians, has been particularly pervasive.

Jones’s style, which has not changed appreciably in the past twenty-five years, except for some sporadic, and pardonable, middle-aged heaviness, is elegant and subtle. As an accompanist, he provides a cushion of air for his associates to ride on. Primarily, this is achieved by his high-hat technique. His oarlocks muffled, he avoids the deliberate chunt chunt-chunt effect of most drummers by never allowing the sound of his stick striking the cymbals to be audible, and instead of ceaselessly clapping his cymbals shut on the traditionally accented beats he frequently keeps them open for several beats, producing a shooshing, drifting-downstream quality.

Jones’s style, which has not changed appreciably in the past twenty-five years, except for some sporadic, and pardonable, middle-aged heaviness, is elegant and subtle. As an accompanist, he provides a cushion of air for his associates to ride on. Primarily, this is achieved by his high-hat technique. His oarlocks muffled, he avoids the deliberate chunt chunt-chunt effect of most drummers by never allowing the sound of his stick striking the cymbals to be audible, and instead of ceaselessly clapping his cymbals shut on the traditionally accented beats he frequently keeps them open for several beats, producing a shooshing, drifting-downstream quality.

Jones’s high-hat seems alternately to push a soloist along, to play tag with him, and-in the brief, sustained shooshes-to glide along beside him. His high-hat also varies a good deal according to tempo. At low speeds the cymbals sound like quiet water ebbing. At fast tempos they project an intensity that is the result of precision rather than the increase in volume displayed by most drummers. The rest of the time, Jones carries the beat on a couple of ride cymbals, on which – as opposed to the tinsmith’s tink tink-tink of many drummers – he gets a clean, pushing ring. All of Jones’s cymbal-playing is contained by spare and irregular accents on the bass drum and the snare, the latter of which he employs for rim shots that give the effect of being fired at the soloist’s feet to keep him dancing. On top of all this, these devices form an unbroken flow; each number – pneumatically supported – comes through free of the cracks and breaks that drummers often inflict in the belief that they are providing support. Jones’s brushes have been equaled by only a few drummers. They are neat, dry, and full of suggestive snare-drum accents, and when used on cymbals often seem an embellishment of silence rather than a full-blooded sound.

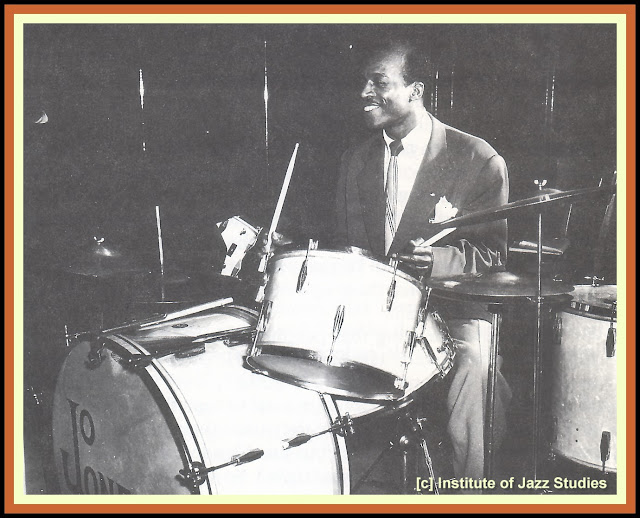

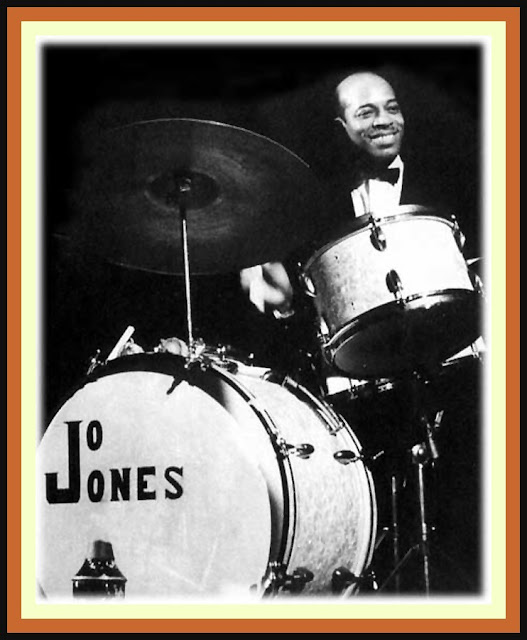

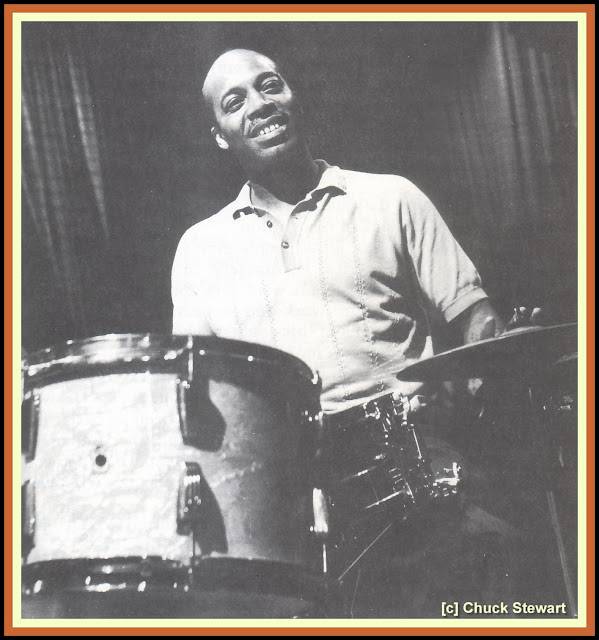

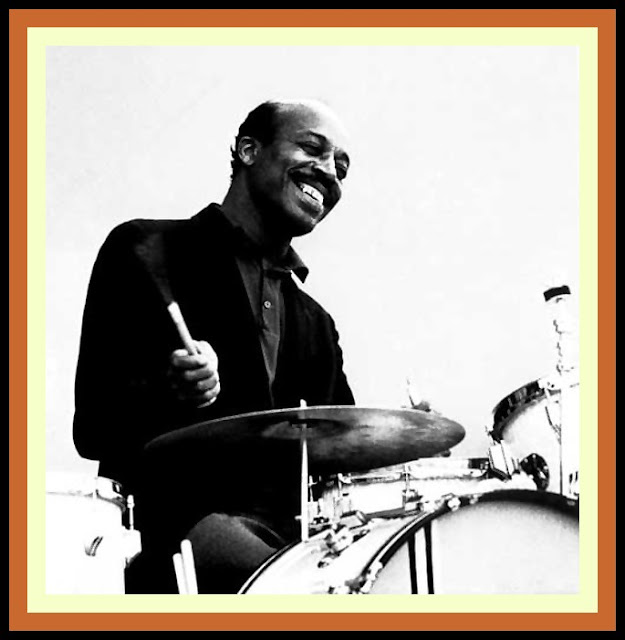

Jones is the embodiment of his own playing. A handsome, partly bald man whose physique resembles a tightly packed cigar and who moves in a quick, restless way, he smiles continually when he is at work, in a radiant, everything-is-fine-at-home fashion. Although he sits very still behind his drums (remember the demonic posturing of Gene Krupa?), his hands, attached to waving undersea arms, flicker about his set and his head snaps disdainfully from side to side, like a flamenco dancer’s.

Jones is the embodiment of his own playing. A handsome, partly bald man whose physique resembles a tightly packed cigar and who moves in a quick, restless way, he smiles continually when he is at work, in a radiant, everything-is-fine-at-home fashion. Although he sits very still behind his drums (remember the demonic posturing of Gene Krupa?), his hands, attached to waving undersea arms, flicker about his set and his head snaps disdainfully from side to side, like a flamenco dancer’s.

His solos, which have recently increased in length and variety but without losing any of their structure, sometimes begin with the brushes, which tick and polish their way between his snare drum and his tom-toms in patterns frequently broken by punching pauses. (Jones’s solo brushwork – stinging and nimble – suggests, in sound and figure, that ideal of all tap-dancing, which great tap-dancers always seem headed for but never quite reach.) After a while Jones may joggle his high-hat cymbals up and down with his foot, while switching to drumsticks, and launch into riffling, clicking beats on the rim of a tom-tom as well as on its head (he may muffle it with one hand, achieving the sound produced by kicking a full suitcase), interspersed with sudden free tom-tom booms. He will then drop his sticks, under cover of more high-hat joggling, and go at the tom-toms with his hands, hitting them with a finger-breaking crispness. More high-hat, and he will fall into half time and, sticks in hand again, tackle the snare drum, at which he is masterly, starting with a roll as smooth as hot fudge being poured over marble. Gradually loosening the roll with stuttering accents, he will introduce rim shots – a flow of rolling still intact beneath – spacing them with a breath-catching unevenness, and then, in a boomlay-boom fashion, begin mixing in tom-tom strokes until the tom-toms take over and, in turn, are broken by snippets of snare-drum beats. Jones will slowly subside after returning to the snare for a stream of rapid on-beat strokes, and – an eight-day clock running down – end with a quiet bass-drum thump. There have been no cymbal explosions, repetitions, or dizzying, narcissistic technical displays. One has the feeling, in fact, of having heard distilled rhythm.

Three of Jones’s recent efforts – “The Jo Jones Special” (Vanguard), “Jo Jones Trio” (Everest), and “Jo Jones Plus Two” (Vanguard) – are sufficient samplers of his work. The first record is valuable largely for two takes of “Shoe Shine Boy,” in which the old Basie rhythm section is reassembled, along with Emmett Berry, Lucky Thompson, and Benny Green. (Nat Pierce is on piano in four of the five other numbers, and for the last there is an entirely different group, composed of – among others – Pete Johnson, Lawrence Brown, and Buddy Tate.) The two versions are done at medium-up tempos, and are just about equal in quality. Thompson and Berry are in commendable form, but the rhythm section is priceless. Listen, in the first take, to the way Jones switches from joyous high-hat work behind Basie’s solo to plunging, out-in-the-open patterns on his ride cymbal when the first horn enters; to Basie’s down-the-mountainside left hand near the end of Thompson’s first chorus; and to Jones’s four-bar break on his snare drum at the close of the number, done with sharply uneven dynamics that make the prominent beats split the air. There is also a rendition of “Caravan,” by the alternate group, in which Jones takes a tidy solo, complete with mallets on the tom-toms, bands on the tom-toms (here, a plopping sound like that achieved by hooking a finger into one’s mouth, closing the lips, and drawing the finger abruptly out), and oil-and-water patterns on the snare with sticks.

Three of Jones’s recent efforts – “The Jo Jones Special” (Vanguard), “Jo Jones Trio” (Everest), and “Jo Jones Plus Two” (Vanguard) – are sufficient samplers of his work. The first record is valuable largely for two takes of “Shoe Shine Boy,” in which the old Basie rhythm section is reassembled, along with Emmett Berry, Lucky Thompson, and Benny Green. (Nat Pierce is on piano in four of the five other numbers, and for the last there is an entirely different group, composed of – among others – Pete Johnson, Lawrence Brown, and Buddy Tate.) The two versions are done at medium-up tempos, and are just about equal in quality. Thompson and Berry are in commendable form, but the rhythm section is priceless. Listen, in the first take, to the way Jones switches from joyous high-hat work behind Basie’s solo to plunging, out-in-the-open patterns on his ride cymbal when the first horn enters; to Basie’s down-the-mountainside left hand near the end of Thompson’s first chorus; and to Jones’s four-bar break on his snare drum at the close of the number, done with sharply uneven dynamics that make the prominent beats split the air. There is also a rendition of “Caravan,” by the alternate group, in which Jones takes a tidy solo, complete with mallets on the tom-toms, bands on the tom-toms (here, a plopping sound like that achieved by hooking a finger into one’s mouth, closing the lips, and drawing the finger abruptly out), and oil-and-water patterns on the snare with sticks.

Jones is accompanied on the trio records by Ray and Tommy Bryant. Although the first record is crowded with twelve numbers, which seem, be cause of their brevity (the kind of brevity that smacks of the nervous a.-and-r. man), more like suggestions than complete numbers, there are brilliant instances of Jones’s brush work. These occur in a fast blues, “Philadelphia Bound,” into which Jones injects some fine high-hat work, particularly behind the bass solo; in the slower “Close Your Eyes,” in which his first four-bar break is taken in a startling and absolutely precise double time that conveys to the listener that sense of pleasant astonishment unique to good jazz drumming; and in the leisurely “Embraceable You,” in which Jones washes discreetly and ceaselessly back and forth on his snare. On the second trio record, which, surprisingly, is far inferior acoustically to the Everest L.P. (Vanguard’s production methods are usually impeccable), Jones develops his “Caravan” solo, in a hundred-miles-an-hour version of “Old Man River,” by taking a four-minute excursion in which be uses the brushes, sticks on muffled tom-toms, sticks on open tom-toms, hands on tom-toms, sticks on snare and tom-toms, and a soft ending with sticks on the snare. Jones is exemplary in the remaining eight numbers, both in briefer solos and in his accompaniment. He also allows a good deal of space to Ray Bryant, lending him the same heedless, sparkling force he grants everyone.”

The recordings reviewed by Whitney involving the Bryant Brothers and Jo have all been released on CD entitled The Essential Jo Jones [Vanguard 101/2-2], a compilation that also contains six tracks from the Vanguard LP The Jo Jones Special that features many of Jo’s buddies from the Basie Band such as trumpeter Emmett Berry, trombonist Benny Green, and tenor saxophonist Lucky Thompson. Freddie Green on guitar and Walter Page on bass, is old rhythm section mates, are on these cuts and Count Basie makes an appearance on Shoe Shine Boy.Here are excerpts from John Hammond’s insert notes to the Vanguard CD release that indicates the high esteem that Hammond, a noted Jazz impresario, held for Jo:“Jo Jones is not only one of the great drummers of jazz but also a major original artist who has left a permanent mark on jazz history and development. The word “great” is one that this writer always feels a little embarrassed about using in connection with a jazz musician; not that the term isn’t justified, but that it jars so painfully when one thinks at the same time of the insecure existence that is the lot of practically every such performer, including those long celebrated as “geniuses” in books and treatises. When a man is publicly recognized as “Great” it should earn him, one thinks, an opportunity to keep producing his best with an untroubled mind. But such a Utopia has not yet arrived. And still, it is one of the miracles that out of the blind and insane commercial musical world to which jazz is inextricably bound, a world that blows hot one year and cool the next, that hands out bonanzas and blanks according to the caprices of fashion, so much comes forth that is a continual testament to the power of the creative imagination.

The recordings reviewed by Whitney involving the Bryant Brothers and Jo have all been released on CD entitled The Essential Jo Jones [Vanguard 101/2-2], a compilation that also contains six tracks from the Vanguard LP The Jo Jones Special that features many of Jo’s buddies from the Basie Band such as trumpeter Emmett Berry, trombonist Benny Green, and tenor saxophonist Lucky Thompson. Freddie Green on guitar and Walter Page on bass, is old rhythm section mates, are on these cuts and Count Basie makes an appearance on Shoe Shine Boy.Here are excerpts from John Hammond’s insert notes to the Vanguard CD release that indicates the high esteem that Hammond, a noted Jazz impresario, held for Jo:“Jo Jones is not only one of the great drummers of jazz but also a major original artist who has left a permanent mark on jazz history and development. The word “great” is one that this writer always feels a little embarrassed about using in connection with a jazz musician; not that the term isn’t justified, but that it jars so painfully when one thinks at the same time of the insecure existence that is the lot of practically every such performer, including those long celebrated as “geniuses” in books and treatises. When a man is publicly recognized as “Great” it should earn him, one thinks, an opportunity to keep producing his best with an untroubled mind. But such a Utopia has not yet arrived. And still, it is one of the miracles that out of the blind and insane commercial musical world to which jazz is inextricably bound, a world that blows hot one year and cool the next, that hands out bonanzas and blanks according to the caprices of fashion, so much comes forth that is a continual testament to the power of the creative imagination.

In this jazz world Jonathan ‘Jo” Jones, born in Chicago, has worked for many years. He has been a star of undiminished brightness from the years (1936-1948) in which he sparked the incomparable rhythm section of the famous Count Basic band, through his subsequent performances with various combos, and demand appearances on radio, television and record sessions, to today. when he presents his hearers with a jazz of solid integrity, and effervescent flow of fresh ideas.

In this jazz world Jonathan ‘Jo” Jones, born in Chicago, has worked for many years. He has been a star of undiminished brightness from the years (1936-1948) in which he sparked the incomparable rhythm section of the famous Count Basic band, through his subsequent performances with various combos, and demand appearances on radio, television and record sessions, to today. when he presents his hearers with a jazz of solid integrity, and effervescent flow of fresh ideas.

There are many outstanding drummers in jazz, and each has his devoted admirers. But all would agree that Jo Jones belongs among the elect, and there is no list of the drummers who have made jazz history that would not put him at the top or close to it. He combines an incredible technique with lightness, humor and imagination. He single-handedly changed the entire concept of jazz percussion. Great drummers like Chick Webb, Gene Krupa and even Sid Catlett had provided the rhythm section and the entire band with a driving power and beat. Jo relaxed the drive of the right foot, using it for just the necessary accents, reminding the listener of the beat rather than insisting on it, realizing that one note in the right place could have more effect that a flurry of sound. He added a variety of timbres, establishing the jazz battery of drums as a musical instrument of genuine beauty. It was the perfect counterfoil to the new approach to jazz piano introduced by Basie.

Jones and Basie, with inspired collaboration of Freddie Green on guitar and Walter Page on bass, brought richness of sound and subtlety to jazz rhythm, providing at the same time an unequaled lift and support for the soloists.”

Thankfully, Burt Korall has included a 46-page chapter on Jo in his Drummin’ Men: The Heartbeat of Jazz – The Swing Years [New York: Schirmer Books, 1990, pp. 117-163]. And while this is far too much information for the purpose of this profile, the editorial staff at JazzProfiles has used Burt’s chapter to put together the following brief synopsis of Jo’s career and some of the qualities of mind and manner that made him unique.© Burt Korall, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

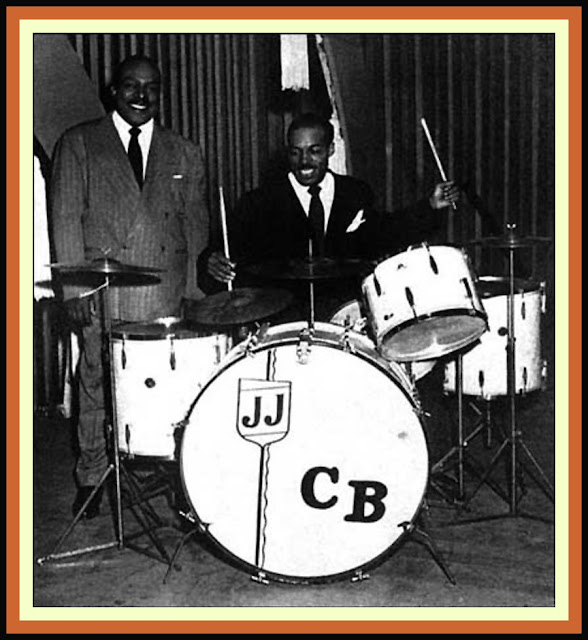

Pictures of Jo Through the Years

Pictures of Jo Through the Years

“Jonathan David Samuel Jones was born October 7, 1911, in Chicago, the son of Samuel and Elizabeth Jones.

Jo always wanted to learn, to be able to give more and more of himself. Because he was by nature a curious and highly sensitive person, with a capacity for absorbing what he saw and heard, Jones assimilated and integrated what he experienced musically. The process was never-ending; that’s why Jones never got “old” as a player. He also used what he learned in his own way. He wasn’t a copy.

Growing up during the 1920s, Jo Jones was on intimate terms with the growth and development of multiple types of popular music and entertainment, He was there, taking it all in, participating: he traveled around the country in carnivals and vaudeville, medicine shows and circuses; later, with bands and groups, he added to the sum of his knowledge. Responsive to and respectful of those who really knew the field, he became an informed, increasingly colorful figure-sure of his ground, seemingly always putting others to the test.

An artist who knew how to manipulate audiences, Jo Jones was a performer. How he dressed, how he carried himself-everything was part of the impression made, he said.

He and his contemporaries were “show business” because that’s the way it was when they were coming along. Though many things about Jones changed with the years, the way he “performed” in front of an audience remained unchanged.

Like Count Basie, his great friend and longtime employer, Jones was completely and thoroughly stage-struck. He enjoyed being around musicians and performers, theaters, clubs, and concert halls, and loved anything that had to do with music and entertainment. He relished talking shop. More than most, he cared for and nurtured young players. Jones was deeply proud of being a musician and realized his responsibility to up and coming musicians.

Despite protestations to the contrary, he never really thought seriously about being anything but a performer. His fascination with the business was permanent. His need to play and be a part of music never left him-even as life came to a close.

He once said: “I want to play twenty-six hours a day, even though I know I need sleep. I don’t want to go near music when I can’t play. I sit there and the palms of my hands are perspiring. It’s a real feeling of frustration.”” [p. 126] …

“It was Jones’ feeling that other musicians missed a lot by not having the benefit of widespread experience. At the close of his life, he often said that Roy Eldridge was one of the few remaining players who had “gone to the same school.” Only Eldridge had shared with Jones the wonder of travel and the diversity of show business. The others “never saw the people … they didn’t hit the forty-eight states-villages and hamlets,” he declared. “After World War II, it got so they could get an airplane and they never saw nothing!”

As vaudeville, carnivals, circuses, and other traveling shows felt the effect of talking pictures, radio, and recordings, it became apparent to Jones that the future was elsewhere. Because of the change in the entertainment business and the response of people to it, Jones became increasingly involved with drums and the performance of music with bands.

As vaudeville, carnivals, circuses, and other traveling shows felt the effect of talking pictures, radio, and recordings, it became apparent to Jones that the future was elsewhere. Because of the change in the entertainment business and the response of people to it, Jones became increasingly involved with drums and the performance of music with bands.

From the late 1920s until linking up with Count Basie in Kansas City in 1934, Jones played his way through a number of bands. He traveled a good deal of the time, using Omaha as his center of operations, all the while becoming immersed in what was happening in music through the Midwest and Southwest.

Jones set a pattern that he followed to the end of his life. Wherever there was a prospect of great music being made, he turned up. He found out, or instinctively knew, where the great sessions would be held in any city or town. He played piano, vibraphone and drums, depending on what was necessary and how he felt. He soon realized that he could be most expressive on the drum set. By the time he joined Basie, Jones had forsaken the other instruments for the most part. Besides, “being a drummer paid better.”

Jones didn’t talk much about playing with the pre-Basie bands. But he indicated that performing with the Ted Adams Band, Harold Jones’ Brown Skin Syncopaters, the Grant Moore Band, the Jap Allen Band, the famed Bennie Moten Ensemble, and Lloyd Hunter’s Serenaders-with whom he made his first record in 1931-helped him develop his distinctive manner of playing.

The style he brought to the Basie band was a product of “the people he rubbed elbows with” and the parts of the country in which he did his performing and listening. The Midwest and Southwest, where his activity was centered during the pre-Basie years, were geographically open areas. It is not incidental that the way bands and individual players from these two sections of America expressed themselves often reflected the spaciousness of the areas. The rhythm was generally looser and lighter than in other places. Drummers allowed the beat to flow, so the rhythmic line straightened out, and ultimately became a rolling 4/4 in the Basie band.” [p. 134]

“The performers of the Midwest and Southwest were noted for their rhythmic invention and change. rhythmic invention and change. During the 1920s and the first years of the 1930s, there was a progressive modification of the pulse of Midwestern and Southwestern bands. One has only to listen to the early Bennie Moten recordings on Victor–cut in the 1920s-and the 1932 session for the same label by this premier Kansas City band. The time feeling moves from two beats to the measure to straight four. Other influential bands within this general territory, such as the much-admired ensemble led by Alfonso Trent, and certainly Walter Page’s Blue Devils, were going in the same direction as Moten. They were starting to relax and swing.

Jo Jones was in the midst of the turbulence and creativity in these areas, moving as he did from band to band. What was being experimented with in the Midwest and Southwest would, within a few years, affect the entire musical community from coast-to-coast. On a recording by the Grant Moore band, “Mama Don’t Allow No Music Playing Here” (Vocalion, 1938) are bass drum “bomb” patterns (by Harold Flood) that became common in the mid-1940s. Willie McWashington, the drummer who preceded Jo Jones in the Bennie Moten band, was also experimenting. “He played ‘stumbles’ they now call them bombs. He made that connection between the interlude and the out chorus. Nobody could drop it in the bucket like him,” Jones said. Though Roy Eldridge said that Chick Webb was among the first to “shoot bombs,” and others claim Kenny Clarke was a primary pioneer when it came to bombs and snare and bass drum coordination, it was in the bands of the Midwest and Southwest that this rhythmic idea initially took form.” [p. 135]

[Quoting drummer Cliff Leeman]: Jo was sitting up there above the band, smiling and cooking. The band was on fire. Basie had found the recipe and Jo was a key part of it.

[Quoting drummer Cliff Leeman]: Jo was sitting up there above the band, smiling and cooking. The band was on fire. Basie had found the recipe and Jo was a key part of it.

Let me tell you, the band became unbelievable. You never felt anything like that! Jo scared the life out of me. I had never heard anyone play that way in my entire life.

Jo Jones had a great influence on every drummer who heard him, particularly in those early years. He played the high-hat with so much finesse. He did so much on it that he turned it into an independent instrument. So many techniques and touches for the hat are his creations. Jo was the first person I ever heard keep time on a closed high-hat while developing counterpoint-in-rhythm with his left hand on the high-hat stand. So many things: the feeling of variation he brought to high-hat playing-how he changed the accents and the feel of the dotted eighth and sixteenth rhythm without interrupting the flow. His little kick beats on the bass drum behind Basie’s piano-so unusual for the time. The way he tuned his drums, to intervals, also was a plus. His drums had an open, un-muffled sound. This sort of tuning is difficult for many drummers because it demands great control of the hands and the right foot. The tuning worked well for him; he found he could get out what he wanted to say because the situation was so challenging.

One of Jo’s most charming bits of business was a thing he did with his right heel. He kept time with it on the floor, combining this sound with what he did on the high-hat. Frequently he would take his foot off the bass drum pedal and use the clicking of the right heel on the floor, alone, as an extra bit of color.

While playing brushes, he’d sweep with the left hand and play a shuffle beat with the right. it was a particularly powerful technique when the tempo was up there-real fast. The beat became so strong. It wasn’t the kind of shuffle beat you associate with bands like Jan Savitt; it had the feeling of a triplet while retaining something of the shuffle. It made you think of a tap dancer. So many great drummers have been tap dancers and come from that tradition: Jo, Big Sidney [Catlett], Buddy [Rich], Louie Bellson.

It’s hard to believe that Jo did all that great stuff on drums [that were] held together with ropes and on cymbals that were just awful. Until Jo became more widely known, and replaced them, he had a rag-tag bunch of drums and cymbals. Still he made them sound.

His ideas and some of the things he played had a base in the past. But a large number of his techniques, patterns, concepts did not come from any place or anyone. They were original with Jo Jones. I can only say about Jo what you have often written about Buddy Rich, “There will never be another like him.”” [pp. 142-43]

“Jo knocked out a lot of people. One of the most important was music man John Hammond. He was so impressed that he used his influence to thrust Jo, Basie, and the rest onto a larger stage, bringing them to a nationwide audience.” [p. 140]

“’The All-American Rhythm Section’ of Basie, Page, Green, and Jones had its own recipe. Relaxing, being natural, responding consonantly and with feeling to the music-all of this gave the section distinction. The section blended flow and interaction, flexibility and freedom, bringing to the Basie music a lightness and a provoking sense of pulsation that carried one along.

“’The All-American Rhythm Section’ of Basie, Page, Green, and Jones had its own recipe. Relaxing, being natural, responding consonantly and with feeling to the music-all of this gave the section distinction. The section blended flow and interaction, flexibility and freedom, bringing to the Basie music a lightness and a provoking sense of pulsation that carried one along.

Very simply, the section swung as none had before, providing a potent example of what could be done if rhythm players moved in the same direction. The beautiful part, though, was that each person in the section never forgot who and what he was, or what a variegated role his instrument could play.” [p. 146]

“The years with Count Basie formed the core of his musical life. Subconsciously, he compared everything before and after with the Basie experience.

In many ways, Jones never left the band. Until the end of his life, there was that link with Basie. In the mind of the public and many of his colleagues, Jones remained Basie’s drummer, despite the fact he played so well with others and on his own.

In spirit, Jo and Basie were together until the pianist’s death in 1984. The love and respect Jones had for his old friend and former employer often were quite touching. As Basie wound down his life, encumbered by illness, Jo kept at him to slow down, in his typically gruff manner: “All the man has to do is maybe ten concerts a year. He could get Pep [Freddie Green], a bass player, and me and not work so hard,” the drummer insisted. “But he has to have that band and travel all the time. No need for that at this point!” Every time he discussed Basie’s schedule, Jo revealed his concern for what might happen to his buddy, his deep voice sharpening into an exclamation point.

Jo found it difficult to view Basie in a mechanical wheel chair. He only wanted to remember the glory years when everything was in a good groove.” [p. 149]

Jo found it difficult to view Basie in a mechanical wheel chair. He only wanted to remember the glory years when everything was in a good groove.” [p. 149]

Less than a year later, on September 3, 1985, Jo was gone, too.

MUSICIANS/OTHER JAZZ LUMINARIES SHARE THEIR MEMORIES OF JO

JOHN LEWIS [pianist, composer-arranger, funding member of the Modern Jazz Quartet]: “You heard the time but it wasn’t a ponderous thing that dictated where the phrases would go. The band played the arrangements and the soloists were free because the time didn’t force them into any places they didn’t want to go.”

JOHN LEWIS [pianist, composer-arranger, funding member of the Modern Jazz Quartet]: “You heard the time but it wasn’t a ponderous thing that dictated where the phrases would go. The band played the arrangements and the soloists were free because the time didn’t force them into any places they didn’t want to go.”

GEORGE WEIN [pianist, impresario who was responsible for producing the Newport Jazz Festival, record producer]: “Jo Jones may have been the most important drummer in the history of jazz.”

IRV KLUGER: “Jo created colors, laid down the down beats and up beats, and brought the [Basie] band in. A revolutionary change had taken place. The Basie feeling was so different from the 4/4 thumping of other sections. Jo’s cymbals, the guitar and the bass walking together, the plinking of Basie and the way he edged in his left hand once in a while – it just lightened everything up and made the jazz rhythm section come to the fore. What these guys did was very difficult to imitate. You had to be so fine. You had to know why you were there.

GUS JOHNSON [drummer]: “I never saw anything like it, the way he was with those brushes. It was smooth as you’d want to hear anybody play, and it was just right easy. He was smiling, doing little bitty things, and he wasn’t working. Jo’s personality and everything knocked me out!”

DAN MORGENSTERN [Jazz writer, Director of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University]: “The effortless grace of the movements, on or off the stand, bespeak his early days as a dancer, just as his solo work may sometimes remind of the fascinating patterns created by the masters of the vanishing art of jazz tap dance.”

LOUIE BELLSON [drummer, composer-arranger, big band leader]: “ As Buddy Rich said – and I agree – if you have to choose one guy it would be Jo Jones. When he came out with the Basie Band, it was if we had been waiting for him. Drummers listened and said: ‘Yeah, that’s where it is. That’s the way a drummer should sound.’ Jo brought fluidity – a musical, legato feeling – to drumming. He also showed us how to set up a band for the finale – the shout chorus. When he played that four bars it was like saying, “Here it is!”

LOUIE BELLSON [drummer, composer-arranger, big band leader]: “ As Buddy Rich said – and I agree – if you have to choose one guy it would be Jo Jones. When he came out with the Basie Band, it was if we had been waiting for him. Drummers listened and said: ‘Yeah, that’s where it is. That’s the way a drummer should sound.’ Jo brought fluidity – a musical, legato feeling – to drumming. He also showed us how to set up a band for the finale – the shout chorus. When he played that four bars it was like saying, “Here it is!”

EARL WARREN [lead alto player with Count Basie 1937-45]: “During the heyday of the Basie Band, it was essential – certainly when you played theaters – for the drummer to play an extended, interesting solo – not a lot of noise. Jo came up with some of the sharpest drum solos I ever heard. His vehicle was ‘Prelude in C Sharp Minor,’ a Rachmaninov thing. Jimmy Mundy made an arrangement together for him.

Jo put together a composition each time he played that feature. What he did was tasteful and very rarely did he go over the same ground twice. His solos could begin on any part of the set. He moved all around. I particularly liked what he did on the tom-toms.

When he got to the high-hat and the cymbals – that was the climax. He worked the high-hat, made it talk, then went up on the cymbals, mixing colors and patterns.”

MEL LEWIS [drummer, co-leader of the Thad Jones Mel Lewis Orchestra later to become the Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra, both forerunners of the current Village Vanguard Jazz Orchestra]: “Of course, Jo played the high-hat for Pres. But he did something else for him … and only for him. He did what he called his ‘ding, ding-a-ding’ on a small, heavy cymbal sitting on a spring holder that was mounted very low on the right side of the bass drum. It had a sound that carried and surrounded Pres.

MEL LEWIS [drummer, co-leader of the Thad Jones Mel Lewis Orchestra later to become the Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra, both forerunners of the current Village Vanguard Jazz Orchestra]: “Of course, Jo played the high-hat for Pres. But he did something else for him … and only for him. He did what he called his ‘ding, ding-a-ding’ on a small, heavy cymbal sitting on a spring holder that was mounted very low on the right side of the bass drum. It had a sound that carried and surrounded Pres.

Jo said that it was really the beginning of ride cymbal playing for him. There might have been others, maybe Dave Tough, who played time on a cymbal this way. But I think that Jo was the first one who loosened things up. He was a pioneer when it came to playing what is now called a ‘ping’ cymbal. The dotted eight and sixteenth rhythm was clearly stated and felt, yet floated, the shimmer of the cymbal providing a cushion for the player or the band. I had never heard anyone do that before Jo. It knocked me out.”

JOE NEWMAN [trumpeter who came to fame as a featured soloist with the Basie Band]: “As a player, Jo had extraordinary style – so much personality. That million-dollar smile of his would light up a stage. What he did went far beyond showmanship. He really knew how to fire up the band. And he did it his own way.”

“Jo Jones was like Louis Armstrong. He did a lot of things first. Techniques and attitudes that today’s musicians take for granted Jo developed.”

ROY ELDRIDGE [one of the most influential trumpet players in the history of Jazz who was featured with a number of Swing Era Big Bands]: “You know one thing that people overlook about Jo’s playing in the Basie Band? His bass drum. He didn’t stop playing it, as some say. He kept a light four going, giving a bottom to the rhythm. Drummers in those days used to tune their drums to a G of the bass fiddle. And the way they used their bass drum didn’t come out boom, boom, boom, but just blended with the bass. The guitar was also playing four, right? So everything was going along the same course, together!

EDDIE DURHAM [trombonist, guitarist, composer-arranger who performed with a variety of Swing Era Big Bands]: “Jo was a master at setting tempos. I think that Basie learned a lot from Jo Jones.”

HARRY EDISON [Known as “Sweets” for the beautiful tone he got on the trumpet was a long-time member of the Basie Big Band, Jazz At The Philharmonic Tours and leader of his own groups]: “It used to send chills up me every night when I’d hear that rhythm section. The whole band would be shouting, you know. And we’d go to … the middle part, the bridge, and all of a sudden … everybody would drop out but the rhythm section. Oh, my goodness, I’ve never heard a band swing like that.”

JOHN HAMMOND [legendary Jazz impresario, talent scout and the man responsible for bringing Count Basie from Kansas City and establishing him in New York]: “All kinds of drummers came to hear Jo at Roseland [the ballroom in NYC where the Basie band was performing] in 1936 and, later, in 1938 and 1939 at the Famous Door on 52nd Street. And he was as much a sex symbol as Gene [Krupa]. Handsome, a shade arrogant, a man with a great smile. Jo had the chicks just falling over him.”

JAY McSHANN [long-time, Kansas City resident band leader who gave Charlie Parker’s career an earlier start]: “Jo Jones had that thing, that swing that everybody dug so much. All the drummers ‘round town learned from him. Jo could play with sticks and then brush you into bad health. Like the other drummers out there who could really play, Jo was relaxed and not too technical. His rhythm was light and natural. It was there, easy to feel. It got you going. See, it wasn’t ‘right to it, right to it, right to it,’ you understand? It was somewhere between tight and loose. KC rhythm might seem straightforward. But it’s really sophisticated and subtle.”

His rhythm was light and natural. It was there, easy to feel. It got you going. See, it wasn’t ‘right to it, right to it, right to it,’ you understand? It was somewhere between tight and loose. KC rhythm might seem straightforward. But it’s really sophisticated and subtle.”

LOUIE BELLSON: “I remember one of the last jazz festivals in Newport, George Wein decided to get all the drummers he thought were top echelon at the time. Buddy [Rich] was there Mel Lewis, Elvin Jones, Roy Haynes, maybe two or three other players [including Louie]. Buddy did his thing, pulling out all the stops. I did everything I could with two bass drums. Elvin played real well. Everybody just – boom! – played hard and creatively.

Came time for Jo Jones; he went out with a high-hat and pair of sticks and tore everybody apart. We all threw up our hands and said, ‘Okay, you got it, man. That’s all.’ No drum set. Just the high-hat. And he broke it up.”

BOB BLUMENTHAL [Jazz writer and historian]: “To put Jo Jones in perspective, how many others in jazz history, both epitomized their own era and made essential contributions to the next?”

BOB BLUMENTHAL [Jazz writer and historian]: “To put Jo Jones in perspective, how many others in jazz history, both epitomized their own era and made essential contributions to the next?”

[All of these reminiscences are drawn from Burt’s book, the Drummers World website and other conversations with Irv Kluger, Mel Lewis and Louie Bellson.]

In 1976, not the best decade for Jazz on records, Norman Granz brought Jo and a bunch of old [and some new] friends together at the RCA Studios in New York and, as a fitting tribute to Jo, recorded Jo Jones: The Main Man [Pablo 2310-799; OJCCD-869-2]. On it Jo is joined by former Basie-ites Harry “Sweets” Edison, Vic Dickenson, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, and Freddie Green. Roy Eldridge partners with “Sweets” to form a brass section and Tommy Flanagan and Sam Jones pair up with Green and Jones in the rhythm section. The group performs six tunes including a measured, slow take on “Goin’ to Chicago Blues and toe-tapping versions of “Dark Eyes” and “Old Man River.”

The group performs six tunes including a measured, slow take on “Goin’ to Chicago Blues and toe-tapping versions of “Dark Eyes” and “Old Man River.”

Producer Norman Granz had this to say about the recording in his insert notes:

“This all-star date was led by the drummer universally regarded as the dean, the daddy, the doyen, the main man. Jo Jones is the source of modern drumming. He was the man who imparted his celebrated ball-bearing smoothness to the All-American rhythm section that he inhabited with Count Basie, Walter Page and Freddie Green. His way of playing drums led to the rhythmic freedom not just for drummers but the soloists who depended on them.”

In August, 2008 the Veterans Committee elected Jo Jones to the Downbeat Magazine Jazz Hall of Fame. And while we are grateful to them for doing so, it would seem that their timing is not nearly as good as Jo’s.